History of Iconography

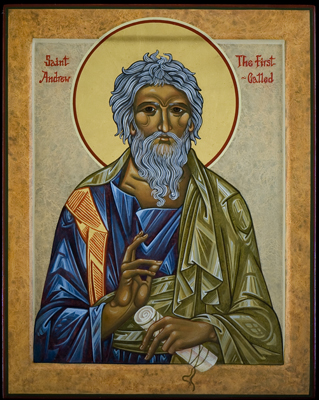

As early as the first century Christian tombs were decorated with pictorial events from the life of Christ. Many have been found in the catacombs at Rome and Alexandria. Often, because of the early Christian persecutions, they comprised of rustic scenes or symbols which had deeper meanings for just the faithful - such as the shepherd sorting out his flock (Christ separating the believers from the pagan) or the Dove (the peace of Christ), the Fish and the Shepherd (symbols of Christ), and the Peacock (symbolic of the resurrection).

The Fathers of the early Church testify to the importance of the icon; that increased widely in liturgical usage throughout the centuries-uninterrupted until the iconoclastic prohibitions (726-843). The icons that survived the large-scale destruction are now mainly in museums, but with a fine collection at Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai. Most show Hellenic influences of idealisation; but with the expressiveness, particularly the eyes, of the Syrians; whereas others show a Roman influence being more lifelike. It was this realism that enabled the iconoclasts to accuse the images of being idolatrous. After icons were reintroduced to the Church a subtle change was made to stop the images from being too realistic and to look more devote and transfigured.

The end of the iconoclastic period saw a vigorous renewal of the decoration of churches with mosaics, and wall and panel paintings. Many schools or studios, mainly monastic, developed particular local styles; many of which have continued to this day.

This is seen particularly in Russia where the Orthodox Church resettled following the spread of the Ottoman Empire. Artists such as Andrei Rublev, Theophanes the Greek and Dionysius, developed iconography to an elevated state, using the Byzantine and Greek ideals of proportion and beauty; creating a perfect harmony between the aesthetic and liturgical.

Unfortunately as time went on iconography, particularly in Russia, became decadent; influenced by the Renaissance art of Italy icons again became humanistic, mainly decorative and sentimental. The aesthetic was lost and again the Church suffered persecution from many quarters. Today, however, iconographers are looking back to Byzantium and the great masters of the past and icons are now being welcomed back into our churches and homes once more.

The History of Icons Icons in Our Lives The Technique of Iconography